(summary of Rosen 2022 chapter by Calvin A. Brown and Ron M. Walls)

Indications for intubation

- Failure to oxygenate or ventilate

- Failure to maintain or protect airway

- Patient’s anticipated course and likelihood of deterioration

Checklist

- Consent/Code Status?

- HOP issues considered (pressor/cpap/bipap)

- Difficult airway? Look in mouth, 3-3-2, remove dentures, range neck (see figure 1)

- Find cricothyroid membrane and mark (see figure 2)

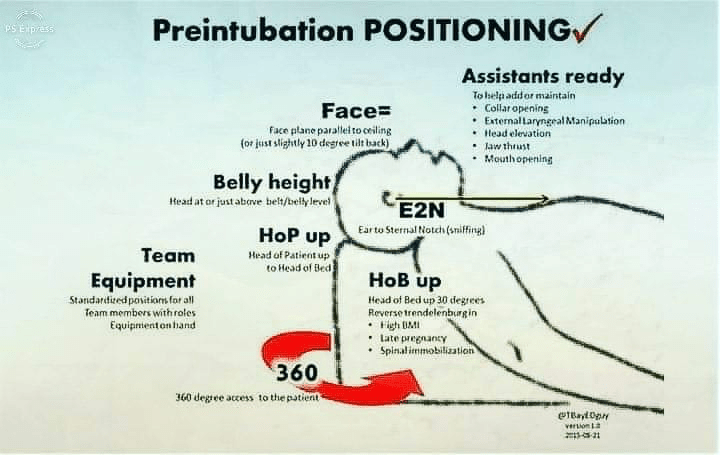

- Position- elevate head, sternal notch to external auditory meatus (see figure 3)

- Nasal canula and nonrebreather flush rate x 3 minutes

- Tube/Vent prep: Check cuff ETT Size 6.5/7.5/8.5, ETT Depth/Vent Setting

- Propofol (10-200mcg/kg/min)/Fentanyl (0.5-1ug/kg IV initial and per hour drip)

- Drugs: +/- Push dose epi

- Suction

- Check cuff on 2 tube sizes

- IV x 2 working

- Bougie/LMA/Scalpel/Lac tray/Betadine

- Backup laryngoscope

Horizontal line from sternal notch to external auditory meatus, couple blankets under shoulders and 6-8 blankets under the head.

3-3-2 rule

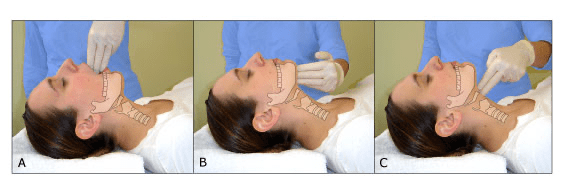

The “laryngeal handshake,” from left to right: 1) hyoid, 2) thyroid, 3) cricoid, and 4) palpation of cricothyroid membrane.

Female versus male external anatomy: The thyroid prominence is evident in the male, whereas the thyroid and cricoid have equal prominence in a female.

Failure of Ventilation or Oxygenation

- ABGs may be misleading, falsely reassuring or falsely concerning.

- In most cases, clinical assessment, including pulse oximetry with or without capnography, consideration of the timeline of the patient’s respiratory emergency, and observation of improvement or deterioration in the patient’s clinical condition will lead to a correct decision.

Failure to Maintain or Protect the Airway

- If airway not patent, establish latency by chin lift, jaw thrust, oral/nasal airway.

- Patient must be able to protect against the aspiration of gastric contents, which carries significant risks for morbidity and mortality

- Patient’s ability to swallow or handle secretions is better indicator of airway protection than gag reflex.

- Evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (GCS <8, intubate adage is not mentioned in chapter, but RebelEM post raises doubts about a strict GCS level).

- In general, a patient who requires a maneuver to establish a patent airway or who easily tolerates an oral airway requires intubation for airway protection, unless there is a temporary or readily reversible condition, such as an opioid overdose.

Anticipated Clinical Course

- Certain conditions indicate the need for intubation due to moderate to high likelihood of predictable airway deterioration, worsening physiologic derangement, or the need for intubation to facilitate a patient’s evaluation and treatment.

- The common thread among these indications for intubation is the anticipated clinical course. In each case, it can be anticipated that future events may compromise the patient’s ability to maintain and protect the airway or ability to oxygenate and ventilate. Waiting until these occur may result in a difficult airway.

- Septic shock: high metabolic demand, myocardial depression, increased peripheral oxygen extraction. combination of ventilatory fatigue, depressed pump function, and the need for directed fluid resuscitation predictably results in the need for intubation as pulmonary vascular congestion, hypoxia, and the work of breathing worsen.

- Multi-trauma patient

- Burn patient

- Neck injury when there is evidence of vascular or airway injury.

- Transfer to another facility/CT with potentially unstable airway

Identification of the Difficult Airway

- ED-based cricothyrotomy rates of 0.5% for all intubations

- ED cricothyrotomy rate is greater than in the operating room, which occurs in approximately 1 in 200 to 2000 elective general anesthesia cases.

- Bag-mask ventilation (BMV) is difficult in approximately 1 in 50 general anesthesia patients and impossible in approximately 1 in 600.

- BMV is difficult in up to one-third of patients in whom intubation failure occurs.

Difficult Direct Laryngoscopy: LEMONS

LEMON Mnemonic for Evaluation of Difficult Direct Laryngoscopy.

- L ook externally for signs of difficult intubation (by gestalt)

- E valuate 3-3-2 rule

- M allampati scale 1&2 easy, 3 still see top of uvula, 4 no uvula

- O bstruction or obesity

- N eck mobility

- S aturation

Difficult to ventilate- ROMAN

- R adiation or resistance to ventilation

- O bstraction angioedema/mass/ludwigs angina, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea

- M allampati, male, mask seal

- A ged

- N o teeth

Crossing the threshold to intubation without paralysis

- Patients with numerous difficult airway characteristics, especially if obstructing upper airway pathology is part of the problem, more often have crossed a threshold of difficulty beyond which neuromuscular blockade would be avoided because a “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate” (CI:CO) failed airway may ensue.

- In these cases, the preferred approach is to use topical anesthesia methods, with titrated parenteral sedation, to achieve intubation without the use of a neuromuscular blocking agent (NBMA).

- This is particularly true when intubation is undertaken with conventional laryngoscopy (versus use of a video laryngoscope or flexible endoscope) or when use of NBMAs would result in immediate physiologic deterioration and instability.

- Patients with refractory hypoxemia or severe metabolic acidosis may be intolerant to even brief periods of apnea. In such patients, an awake approach is preferred, particularly if anatomic difficulty coexists. 4

- Airways predicted to be anatomically difficult when using a traditional laryngoscope may not prove difficult when a videolaryngoscope is used (see later discussion). Occasionally, RSI remains the preferred method, despite assessment that the patient has a difficult airway, as part of a planned approach to airway management. This may include physiologic optimization, use of videolaryngoscopy (VL), and a double setup, in which a rescue approach, such as cricothyrotomy, is fully prepared for immediate use in the event of intubation failure.

- Regardless of the results of a reassuring bedside assessment for airway difficulty, significant challenges may be encountered with intubation and BMV, and the clinician must be prepared for unanticipated difficulty with every intubation.

- Identification of a difficult intubation does not preclude use of an RSI technique. The crucial determination is whether the emergency clinician judges that the patient has a reasonable likelihood of intubation success, despite the difficulties identified, and that ventilation with BMV or an EGD will be successful in case intubation fails.

- Clinical scenarios

- Stridor

- Angioedema

- Can’t open mouth

- Severe acidosis

Delayed Sequence Intubation

- Agitation, delirium, and confusion can confound attempts at preoxygenation when a patient is unable to comply with conventional modes of supplemental oxygenation, such as a face mask or BiPAP.

- DSI considers preoxygenation a procedure and uses dissociative doses of ketamine (1 to 2 mg/kg IV bolus) as procedural sedation to accomplish this.

- A small, ED- and ICU-based multicenter observational study showed post-DSI oxygen saturations significantly higher than pre-DSI levels. There were no noted adverse outcomes or desaturations when intubation eventually took place in this limited case series. 25

- A prehospital investigation that studied the routine use of DSI as part of a multi-interventional bundle (which also included preoxygenation targets and upright patient positioning) to prevent desaturation during airway management showed a 10-fold reduction in rates of peri-intubation desaturation without increased adverse events. 26

- However, this approach is not without some risk, as there have been reports of ketamine-induced apnea during DSI. 27

- However, this approach is not without some risk, as there have been reports of ketamine-induced apnea during DSI.

Awake Oral Intubation

Ideal candidate: Any patient, who is not crashing, with a predicted difficult airway, especially if also a predicted difficult to ventilate.

Medications:

- Glycopyrrolate 0.2mg or Atropine 0.01mg/kg IV

- Lidocaine 4% nebulized at 5lpm over a few minutes

- 2% gargled viscous lidocaine

- Ketamine 20mg aliquots

Additional reference: Emdocs

Pharmacologic Agents

Succinylcholine

- Dose-

- Onset- 45 seconds

- Duration- 6-10 minutes

- Adverse Effects:

- Bradycardia, especially in children

- Contraindications:

- Burns>10% BSA > 5 days after injury until wounds are healed

- Cursh injury > 5 days after injury until wounds are healed

- Stroke/spinal cord injury >5 days until 6 months post-injury

- Neuromuscular disease (ALS, MS, MD) indefinitely

- Intraabdominal sepsis >5 days until infection resolves

- Renal failure IF patient has known or presumed hyperkalemia

Rocuronium

- Dose: 1.2-1.5mg/kg IV (actual TBW) 1.5 faster onset but longer duration

- Onset: 60 seconds

- Duration: 45 minutes (can be reversed by Sugammadex)

- Contraindications: none

Etomidate

- Ideal induction agent: decreased ICP, maintain MAP and CPP.

- Dose 0.3mg/kg IV

- Onset: 30-60 seconds

- Brief myoclonus not relevant if also giving paralytic

- Etomidate less likely to precipitate hypotension than ketamine

Ketamine

- Dose 1.5mg/kg IV

- Indication: awake intubation, acute severe asthma, hypotensive post-intubation

Special Clinical Circumstances

Status Asthmaticus

- Don’t intubate the severe asthmatic, try NIV first.

- Preoxygenate with BiPAP (10/5) unless stopped breathing

- Ketamine DSI if patient delirious and fighting bipap

- You will know if patient is improving within 5 minutes

- Large ETT 8-8.5

- Avoid aggressive bag-mask ventilation

- RSI is the best choice

- Use Ketamine for induction, Rocuronium for paralysis

- Initial settings per Farkas/IBCC

- Pressure-cycled ventilation (PC)

- Respiratory rate of 12 breaths/min

- Inspiratory time (I-time) of 1 second

- Inspiratory pressure of 40 cm, PEEP of 5cm

- FiO2 initially at 60%

- IV epi drip can be tried (start at 5 micrograms/minute and titrate in the 1-15 range)

Hypotension

- Fluids

- Pressors

- Reduced dose of induction agent (Etomidate .1-.15mg/kg)

Elevated ICP/Aortic Dissection

- Larnygoscopy and intubation are potent stimuli for the reflex release of catecholamines which causes a modest increase in BP and HR

- Certain conditions benefit from a reduction in this reflex:

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- SAH

- Aortic dissection/aneurysm

- Ischemic heart disease

- Pretreatment (3 min before intubation) with Fentanyl 3 ug/kg IV safer than higher doses and can be supplemented with an additional dose post intubation if desired. Give over 60 seconds and observe for hypoventilation/apnea.